There’s a junk shop in Lichfield called Quercus of Quonians, its situated down an ancient side street in an equally ancient building. It has the exact musty, old smell you’re imaging right now and is rammed floor to ceiling with anything from bits of old crockery to stuffed crows sat on skulls. For some reason, one of the only things they lock away are the old cameras which is intensely frustrating because not only is everything just thrown on top of other things, you can never, ever see the price of anything.

Their cameras are hilariously over priced. We’re talking £90 for a Zenit 11 which should be about £5 or, special offer, we’ll pay you to take it away for us. Even so, I still pop in reasonably regularly to make sure that nothing interesting has popped up and has been sensibly priced for a few quid.

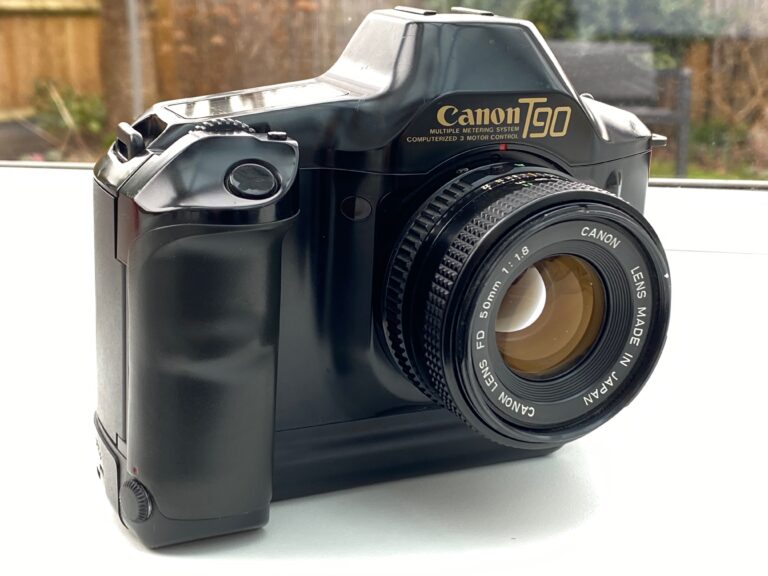

Months ago, I’d spotted a new arrival in the cabinet of crap and spied, through it’s little red window, that it still had a film in it. I couldn’t tell how many frames had been shot and, of course, had no idea of the price. I left it for weeks and weeks until I finally had £10 in my pocket (they refuse to use anything remotely resembling technology, so cash it is) and thought I’d just offer them that and try my luck – and this is how I ended up with a Coronet D-20 and its potentially fascinating payload.

In this post:

- Who were Coronet?

- Revealing the mystery prize

- A clean and spruce up

- A trip to Ghent

- Conclusions and learning

Who were Coronet?

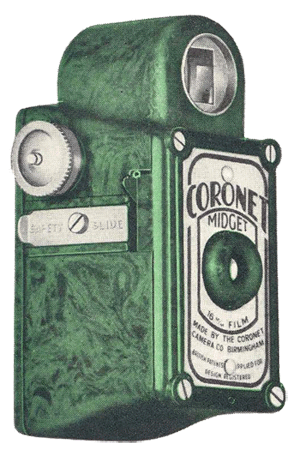

Coronet are very close to home. The company was founded in Birmingham, Great Hampton Street in 1926. Twenty years later they moved down the road to Summer Lane in Aston and remained there until their closure in 1967. Their business model was simple – make and sell the cheapest cameras possible. This was not a company bothered with any kind of luxury.

The Coronet building still stands today, although there doesn’t appear to be any signs of its former purpose and it is, shall we say, not in the nicest place on earth. You can visit it from the safety of your sofa on Google Streetview below:

Coronet almost exclusively specialised in box type cameras and released numerous models all sharing very similar characteristics. The basic principle of each camera was a fixed, metal aperture ring coupled to a swinging pendulum type shutter which we’ve seen before on the Ensign Ful-Vue and very popular on cheap cameras from the 40’s-50’s. This meant that on the most basic models you got fixed focus, one shutter speed (plus “timed” or bulb) and one aperture. Limited doesn’t begin to describe it and early models were even made with cardboard bodies – as such they are somewhat delicate these days if you can pick them up.

Later models were made of Bakelite and metal (as the D-20 is), some came with a lever to shift aperture and, if you were really lucky, a selection of focal lengths that could be selected by twisting the lens. They seemed to produce roll film cameras almost exclusively, usually 120 and 620 but the occasional model such as the Cub used the extinct 828 format which is basically 35mm film in roll format without perforations. You can make this type of film yourself if you get hold of a couple of reels – usually obtained by buying two of the same camera! I’m tempted to pick a few of these up myself.

Coronet are not collectible and as such their prices are rock bottom, often found in bargain bins for £5-10 at most. They did, however, produce one highly collectible model called the “Midget” which goes for hundreds of pounds today. I can’t understand why, it uses 16mm film and was seen as a “discrete” or “spy” camera, but still made to the cheap and cheerful standards Coronet were known for.

Unless I’ve missed something, Coronet never made a 35mm camera and that’s probably because it is far cheaper and more simplistic to make roll film cameras than those which rely on sprocket hole film. There were a couple of bellows type cameras but these also were as basic as they come. When your entire product lineup consists of cameras that, at best, have three shutter speeds and none which used the rapidly evolving 35mm format, I don’t think it’s difficult to see why they eventually ran out of steam in the late 1960’s

Revealing the mystery prize

When I tried the D-20 in the shop, the winding key was spinning but doing nothing at all to actually move the film so would have to wait until I got it home and could fiddle around with it in a dark bag before learning more. The body itself was in really poor shape and, as seems common on these cameras, was covered in rust.

The problem with buying cameras that contain an old film is that people have inevitably opened them up at some point and spoiled the film. The number I see for sale on ebay and then there’s the dreaded photo with the back open, ruining the film, is enough to make a grown camera geek cry. This one didn’t seem to have been opened, though, due to the fact it was well and truly rusted shut. The only risk to the shots on this roll were multiple exposures on the last frame from people testing the camera or just playing about with it. Confidence of recovering some kind of memories from this thing were relatively high.

Taking apart an unfamiliar camera when you can’t see it isn’t the easiest thing in the world, but that was nothing compared to trying to get the film to wind onto the developing spool. Over many, many decades this film had become curled to an extraordinary extent and no amount of bending it in the opposite direction was going to encourage it to flatten out enough. I eventually managed to get it onto a spool after a significant fight, convinced that I’d probably ruined it in the process or at least put some reasonable creases in unfortunate places.

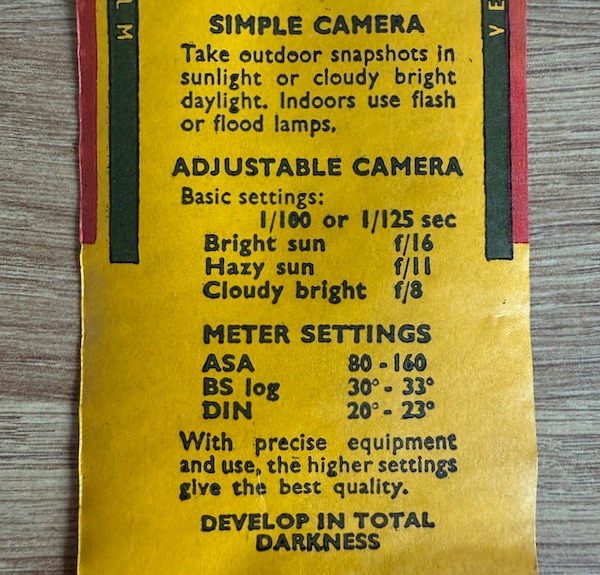

Once out of the dark bag I could see that the film was Kodak Verichrome Pan. I’d never heard of it before now, but it was a very popular and well respected black and white film that Kodak sold in various roll forms, but never 35mm, from the 1950’s (as “Pan” but has roots as far back as the early 1900’s and was officially introduced as Kodak Verichrome from 1931 – see the advert below) until as late as 2002. There is no sensible way to date this film, but there are some clues.

The reels are made of metal rather than plastic and this particular roll is 620 rather than 120. The beginning of the backing paper has some rudimentary shooting instructions:

I’ve found similar images online and people date these films to around 1975. The D-20 camera was introduced around 1950, if we make some simple assumptions it would make sense that this film dates from somewhere around 1970-1980. I cannot imagine why anyone would’ve been actively using a Coronet D-20 box camera in 1980 or later, considering the wealth of cheap, advanced film cameras available from the 1970’s onwards. The inflexibility and disadvantages of the Coronet would surely have driven the owner to better equipment by that point. Roughly 1975 seems reasonable for the probable age of this film.

Verichrome itself was widely regarded, despite being sold as a “snapshot” film. It had insane latitude which made it suitable for these rudimentary types of camera, allegedly having two emulsions – a fast and a slow. Did it, though? I’m not so sure. Either way, the images it produced on 120 and 620 film were of very high quality and showed little grain.

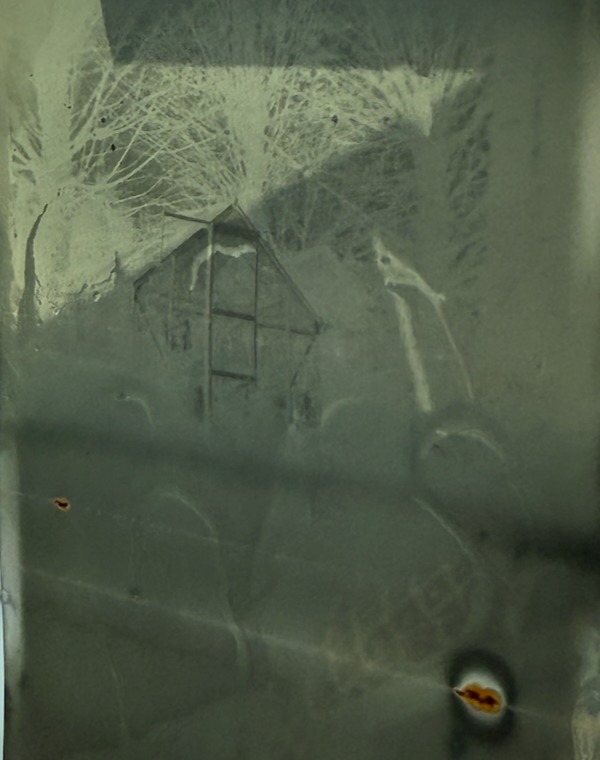

I developed this roll in Rodinal at a dilution of 1:100 for 1 hour and 20 minutes. This is a pretty safe bet for any film when you’ve no idea how to treat it. Stand development has so many advantages, the main one being you always seem to get something no matter how bad the film or exposures were. After fixing and washing, I eagerly pulled the film out of the reel and hung it up.

The film was absolutely knackered. As you’d expect after so many years stuck inside a rusting camera body. The rust had actually transferred itself onto the film and as for pictures….? One. There was one solitary frame. Well, there were three but the other two were a mash up of multiple exposures where someone had obviously been trying to either test or fix the camera before giving up. They’d managed to move it on two frames, though, so God only knows what they were doing.

So much for a treasure trove of lost memories, then. What I actually unearthed was a picture of someones greenhouse that, in the words of many people who all said the same thing, “looks like something out of a horror movie.” You can judge for yourself:

A clean and spruce up

I had never wanted the actual camera and so there were two choices at this point – stick it on a shelf and forget about it or give it a clean up and give it a second chance. I can’t stand just leaving things broken, so a strip down and clean it was. The one thing you can say for old cameras is they are completely serviceable. Everything comes apart easily, parts are accessible and no odd tools are needed to undo special types of screws or similar.

The D-20 couldn’t be simpler, it is quite literally a box with a hole in it and is one up from a pinhole camera. The hardest part of the whole thing was getting the shutter assembly out due to the levers that protrude to the outside of the box. Once that was out, it was plain sailing, The main thing to do was replace all of the light seals as they’d turned to dust and just fell apart on contact. A quick polish up of the lenses, some glue on the viewfinder mirror to stick it back down and it was ready to go back together. I spent a small amount of time with some sandpaper, a fibreglass pen and a polishing tool to get rid of the majority of the rust, but I wasn’t prepared to strip off the textured covers so a small amount still remains.

A trip to Ghent

The D-20 has two apertures – F16 and F22 coupled with a shutter speed of roughly 1/60. I’m not sure how anyone was expected to get well exposed images out of this thing back in a time when ISO 100 would’ve been considered fast. This camera is quite literally a “sunny 16 machine” and it would’ve been pointless using it in anything other than perfect sunny conditions outdoors. I chose to load it up with a roll of “Lucky” film rated at ISO 400 just to give me a chance of getting a roll of usable images out of the other side.

It just happened that I was stopping in Ghent, Belgium for a day as part of a longer road trip and this seemed like the perfect opportunity to give the D-20 an outing that it surely wasn’t destined for. Conditions were good, slightly cloudy but fairly bright nonetheless. Regardless, at F16 as a minimum and a very slow shutter speed, any shots would need to be taken with a very steady hand or rested on a solid surface.

It looks a lot like it was raining quite hard when this picture was taken but I think we all know that those black streaks are scratches in the negative. This is sadly quite typical of really old roll film cameras and if there is the slightest, imperceptible imperfection in either of those rollers or even the film mask then you’ll get scratches all down your film. I had similar with a Kodak Vest Pocket recently and no matter how much I polished, checked, sanded and so on, I couldn’t stop the camera from scratching films.

In retrospect, I should’ve checked for these rough spots when I’d been cleaning the camera up and replacing the light seals. Going back to it now, I can definitely feel rough spots on both the top and bottom of the film mask. Making these perfect again would be no simple task.

What about the positives? Well, the small aperture has certainly helped the image quality and centre sharpness is decent but… the rest is soft as melted ice cream. The edges are particularly hilarious, almost becoming warped in their appearance due to blurriness.

Would people have cared in 1950 about the image quality shown here? I’m not sure they would. Anyone buying a D-20 would’ve done so knowing it was one of the cheapest cameras available and print sizes back then weren’t exactly huge. I think most people would’ve considered these pictures to have a certain charm about them. It wasn’t at all unusual for pictures to come out blurry, out of focus or exhibit softness with cameras of this age – you only need to look at your grandparents picture albums, old war photos and so forth to see the kind of image quality that passed as acceptable back then. Furthermore, when this camera was new, there would’ve been no scratches down the negatives!

I can’t help but think that I was lucky (no pun intended) using ISO 400 film. The conditions I shot this roll in were close to perfection in terms of available light, yet even so I think they’re still under exposed in some frames. How on earth people used this camera with slower film is a mystery. There’s no way that at F16, with a shutter speed of somewhere between 1/60 and 1/125 that many pictures were correctly or reasonably exposed. Lots of pictures must’ve been taken using timed exposures and that just introduces a world of camera shake as it isn’t possible to use a cable release with the D-20.

Perhaps this is where my age and lack of knowledge of this era of photography fail me. Could this be why Kodak claimed their film was sensitive to a monumental degree of latitude? Did film processing labs just automatically compensate for these exposures by pushing the film during development? Was it expertise in the dark room when creating prints? One way or another, I find it hard to believe that people put a roll of ISO 50 or 100 through this and got back a set of 12 prints that looked perfectly fine without some serious adjustments being made somewhere along the line.

Finally, the viewfinder on this camera is really hard to use. It isn’t particularly large and any deviation from the perfect viewing angle gives you the dreaded dark patch or internal reflections that mean you can’t see a thing. Taking pictures is very much a case of pointing vaguely in the right direction and calmly, slowly, pressing the shutter. You do roughly get on film what you saw in the viewfinder, but for critical accuracy it is probably better to give yourself some extra breathing room.

Conclusions and learning

It’s important to remember that I didn’t set out to buy and review an old box camera, especially not one that sold in such vast numbers, is so widely available and so completely undesirable. However, there’s no denying that this camera grew on me, it deserved a second chance and yes, I hate to say it, had a certain charm when using it. The looks you get in a super tourist hotspot, rammed with people using £6,000 DSLR’s, Go-Pro’s and gimbals galore are hilarious when you pop up with your 1950’s tin box. You might as well be taking photos with a rock at that point.

I’m always amazed that such simple contraptions produce any kind of image at all, especially after languishing in antiques shops, damp and hot loft spaces or the bottom of a wardrobe for decades on end. This camera like so many others has suffered a little too much from neglect and it really isn’t worth the money in film to polish out those scratches and bumps, film test it, try again and so forth. I’m not desperate to shoot the camera again and each roll of film costs the same if not more than the camera itself.

The real shame here is the roll of Kodak Verichrome that was left in the camera. The memories it could’ve revealed but didn’t, the lost couple of frames which featured multiple, multiple exposures from people trying to work out why it wouldn’t wind any longer and, do you know what, I cannot work out why it didn’t wind either. The key had clearly slipped out of the film spool, but how that happened is a mystery because it must’ve been properly engaged to load the film in the first place and take that incredible greenhouse shot…

It just goes to show, this kind of purchase is exactly the same as gambling – you win some and you lose some but more often than not, when curious people press buttons and wind winders, you invariably lose. Still, I had a lot of fun with the Coronet and the local connection certainly helped with the motivation to fix and persist with the camera. I’m glad I’ve given it one last hurrah with a trip somewhere nice, but it’s definitely one for the shelf in the garage where cameras go to be not quite thrown away, but probably never used again…

Share this post: