If you look back at old photography magazines you quickly discover that 35mm cameras were fine, but if you wanted to do real photography then you needed to join the exclusive, expensive medium format club. In this world, people don’t shoot off 36 frames with merry abandon, take advantage of automatic modes and *gasp* automatic film winders. No, the medium format photographer is a professional who needs only 12, or maybe even eight frames to do justice to their given subject. For this, they are rewarded with high quality, detailed and print worthy negatives – what picture editor in their right mind would accept 35mm print film?!

Sarcasm aside, medium format really was seen as the logical next step if you were serious about photography and in some cases was an essential investment. If you wanted large prints and the finest quality that showed almost no grain whatsoever, then medium format was the choice you had to make. Medium format negatives are, without doubt, very impressive the first time you see them and they are indeed full of crisp, fine grained detail the likes of which you’d be hard pushed to reproduce in 35mm. Once you see the developed roll, the fact you can only get 12 frames out of a roll that costs the same as a 36 exposure 35mm roll is suddenly forgiven.

There’s just one problem – price. Unlike 35mm SLR’s which saw huge advances in technology and consequently cheaper, ever more capable models kept being released in a never ending price war, medium format models were developed at a glacial pace. Also, like high end sports cars, medium format cameras resolutely held their high value. For reference, in 1990 you could buy a Bronica SQ-Ai for £1300 – that’s £3222 in 2025 and these prices started where the absolute top of the line, professional 35mm SLR’s left off. Not to worry, though, if you didn’t have the money but still wanted to use 120 roll film and were prepared to slum it with technology from the 1930’s, the Russians were here to help!

In this post:

Cheap then, cheap now

Gomz/Lomo are the same company that made the superb and almost unbelievably cheap Cosmic Symbol 35mm camera. I used the slightly more refined Cosmic 35 some time back, a camera that has everything you need to take a picture and absolutely nothing else. Devoid of features it may be, but it’s a rather satisfying camera to use nonetheless and is capable of some relatively nice, sharp pictures under the right circumstances.

The Lomo brand specialised in low end, cheap and cheerful knock offs of other successful camera designs, built to the lowest possible cost. Their strategy was to pile them high and sell them cheap – and sell they did. The Lubitel 166 series probably sold more than all other medium format cameras put together.

The design of the 166 Universal can be traced all the way back to 1949 thanks to the superb SovitetCams.com website. The 166 variant of the Lubitel was launched in 1976, replaced by a the 166B in 1980 and finally the 166U or Universal in 1983. All three cameras from 1976 up until the end of their production in 1994-6 (I find different dates in different places) used the same lens and are effectively the same camera but with some tweaks such as different hot/cold shoes and the removal or addition of a frame counter.

The 166 Universal has only one unique feature when compared to its predecessors in that it came with a 6×4.5cm mask that could be added in the back to give more shots per roll. At least that’s what they sold it as, according to the reviews I can find from 1990, it was more likely introduced to remove the chronic vignetting that the lens produced on 6x6cm negatives. Either way, it’s a nice feature and almost entirely unobtainable with second hand cameras today. Unless you’re very lucky, most of these masks are now lost.

But… Hang on a minute – why was it reviewed in 1990 when the camera came out in 1983? It seems to be because the initial models were only sold in Russia and then years later found their way to British markets. There were many minor variations of the 166U itself which are documented here and it looks like my copy is one of the very last of the line.

Whilst most medium format cameras from the 1990’s would’ve set you back the equivalent of half a years wages, the 166U had a recommended retail price of £22 (£55 in 2025) and could often be found even cheaper. If that were still to much for your budget, you could’ve still picked up the 166B for £15 (£37 in 2025) brand new. Although comparatively very cheap, the 166 is just about one up from a plastic toy camera in terms of build quality so even in 1990 I’d probably have still wanted to wait around until they were on offer rather than parting with £50 for a plastic box with a lens.

Collectible tat

I don’t think I’ll ever understand the “Lomo” trend (not to be confused with the actual brand Lomo) where because something is garbage it has a certain look and feel which is somehow desirable? I don’t see it. There’s no charm in an image which is soft as melted ice cream, with aberrations and vignetting all over the shop because it was taken through a lens made of cheap plastic. Neither is this look “nostalgic.” The idea that years ago we were all running around shooting images with weird colour casts and could only find cameras that had lenses made from old bottle tops is just absurd. This is not a “look” which is accurate or of its time, it is a trend – and an awful one at that which will hopefully die the same death as Instagram filters.

However, there’s no escaping that cameras that were (and still are) seen as toys, or at least the most entry level of machines, are now attracting ever higher prices because someone has decided they have a trendy feel to them or the images created are “ethereal” (rubbish). You can still pick up a Lubitel for about £25 in reasonable, working condition, but there are already one too many comedians on eBay who are trying to shift them for £50 and upwards which for this type of camera is nothing short of madness. Do not pay more than £20 or £30 as an absolute maximum for one of these. Even more confusingly, the 166B commands a higher price – why? It’s the same camera with the same lens and shutter? I will never understand the apparent value of some old cameras.

To put those prices in perspective, you can definitely get yourself a Yashica TLR for around £60 if you’re patient and if you’re not patient you could do a lot worse than the Halina AI which will set you back no more than £20, which is less than the cost of a plastic Lubitel. The bottom line is, prices are crazy when you can get much higher build quality and definitely higher optical quality for less.

I paid £21.46 for mine which was the upper limit that I was prepared to pay for it. I didn’t have to be particularly patient, they’re abundantly available but you get what you pay for and mine was in “reasonably disgusting” condition when it arrived and had to spend some time having an alcohol bath before it was clean enough to use without constantly wanting to wash your hands.

Using the 166

Putting all the talk of plastic and pricing to one side, the Lubitel 166 is actually quite a satisfying camera to use, although it definitely has its quirks. According to reviews at the time, the shutter speeds are accurate up to 1/30 of a second, anything above that is pretty much guesswork as apparently 1/125 is more like 1/60 and it gets worse from there. Bear in mind, this will have been on a brand new copy of the camera, not a 35 year old version. Therefore, it’s perfectly fine to use a bog standard light metering app on your phone to get a rough idea of exposure for each frame.

I tried to shoot most frames at around F8 – F11 as focussing can be critical on TLR’s, especially for close up subjects and that’s why they usually come with a magnifier so you can get the focus bang on. I didn’t really have any focus issues with the Yashica I used a few years back as that had a glorious viewfinder and the magnifier was massive. The Lubitel, on the other hand, has a tiny little flip up magnifier and it’s… not great.

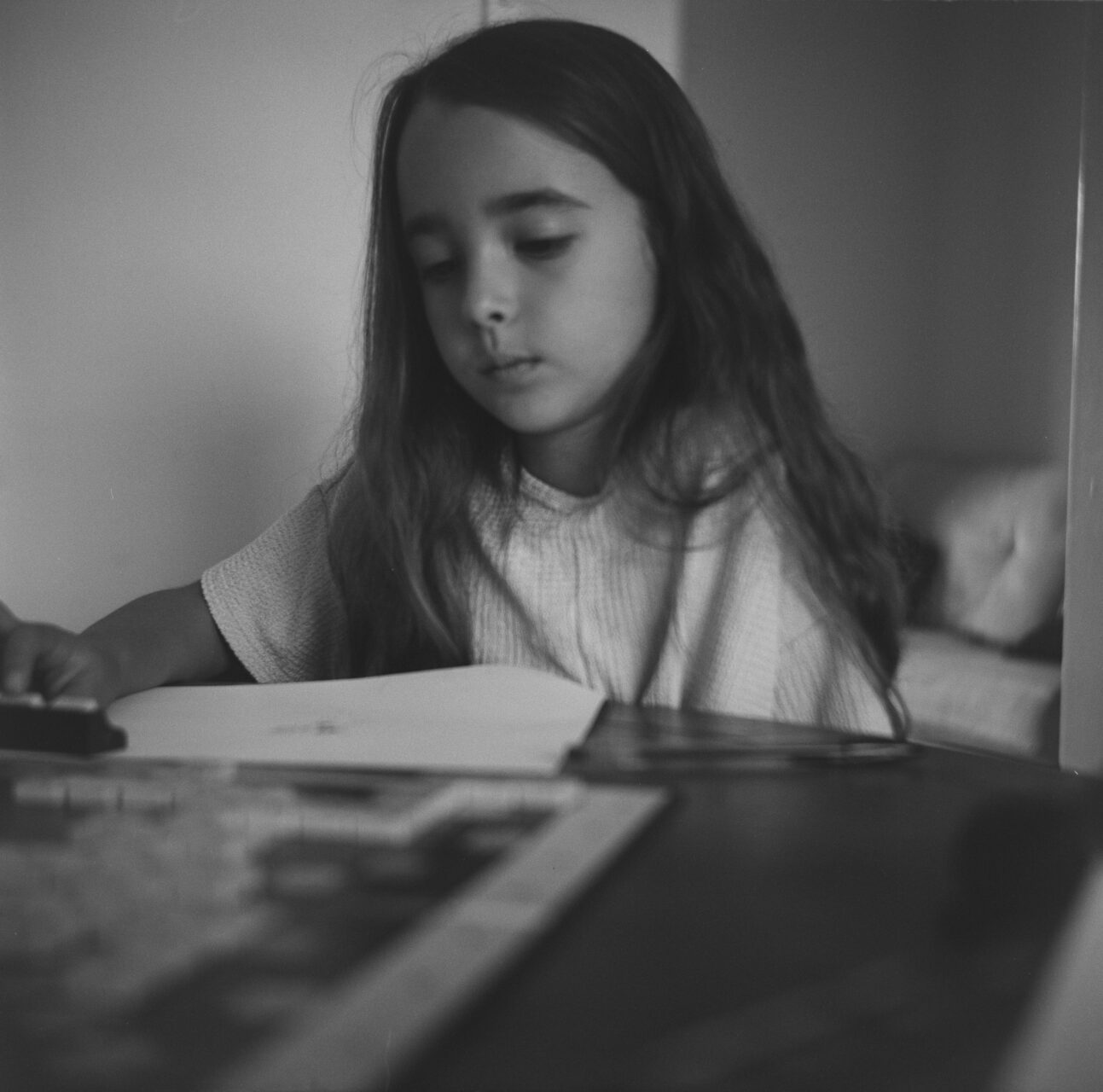

The last shot on the roll was one of my daughter and due to low light, ISO 100 and the indoor setting I was forced to use F4.5. Even at that aperture I had to use about 1/30th as the shutter speed and I spent quite a while trying to confirm focus. I thought it was spot on, but the resultant negative had perfect focus on her shoulder and a blurry face. Although a matter of a few cm, this was enough at such a wide aperture to give a depth of field of only a few cm at such close range.

Why was the focus out? There are a couple of possible causes – she may have moved, it’s a possibility but it didn’t seem so at the time. Next, it could be that I just didn’t dial the focus in perfectly when using the magnifier or, finally, it could be the age old issue that these cameras have where the focus lens and the taking lens become out of sync due to wobbly lens syndrome, slipping a tooth or two on the geared outers or simply that it wasn’t set up correctly from new. This is a difficult and expensive problem to solve because you’ll need to first try to fix the focus using a test chart and then you’ll need to shoot a test roll to confirm. I really don’t fancy spending £8 or so just to confirm focus on a £20 TLR.

If you stick to subjects further away like landscapes and smaller apertures then the results are really quite stunning for such a budget camera with a lens that was known for being relatively awful. If you’re used to 35mm film photography you’ll certainly have experiences of nice and clear, crisp negatives that give plenty of detail. When you get it right on medium format, though, the difference is initially astounding.

And this is dangerous.

Instantly my mind starts thinking – if you can get results like this on the cheapest, most badly built TLR ever, what must results be like on a Bronica, Hasselblad or Mamiya? They suddenly become very desirable and this is really, really bad as the cheapest copies I can find, with a lens, of any of these cameras is more than I spent on my latest DSLR… Oh God.

There are very few controls on the Lubitel and it takes some familiarisation to become natural with it. Finding the aperture lever can be a hassle as it’s quite small and not that obvious at first. There’s no feedback or “stops” on this lever and so you’re just placing it in what looks like the right place each time, which is fine, but you can actually go beyond f4.5 at the wide end and beyond F22 at the stopped down end. It’s not broken, it just lets you do it.

What is broken, on my camera at least, is the self timer lever. Self timers of mechanical shutters are common failures and if yours doesn’t work then it really is best left alone. You can do terminal damage to the shutter mechanism by forcing the self timer, so if it doesn’t work as you’d expect or the manual says, then leave it. Fixing mechanical shutters is beyond most people, let alone those without many boxes of very intricate repair parts. It’s a shame because I did want to use it a few times, but this is not an end of the world situation.

The bad news doesn’t end there. On the plus side, the viewfinder is very accurate. In nearly every frame, I got out of the camera almost exactly what I remembered trying to capture. On the negative side, however, the viewfinder is… weird. If you hold it too close to your face/eyes, it simply doesn’t work. Large parts of the image disappear and you can only see a small circle in the centre of the viewfinder. I know it’s called a waist level finder, but this is the first I’ve ever used where you quite literally have to hold it down by your waistline before you can actually see the image you’re trying to take. It doesn’t take a genius to work out that this is quite inconvenient, especially if something is at eye level. Yes, there’s a “sports finder” that you can use at eye level but it is nowhere near as accurate as the waist level finder.

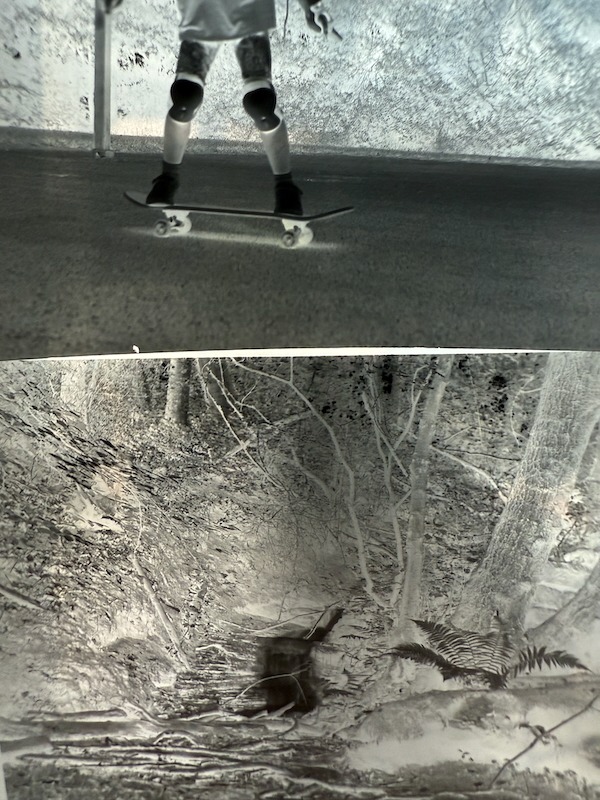

Finally, and this isn’t a Lubitel problem but one of all similar roll film cameras, it is way too easy to accidentally roll a little too far when winding the film and there’s no going back if you do this. At best you get two frames that are basically sandwiched together, at worst you get overlapping images. This is a “me problem” and I just need to slow down and be a little more deliberate when winding on to the next frame.

One nice surprise was that I managed a two second exposure without a cable release, just resting the camera on a solid rock, holding the shutter open whilst counting in my head and hoping for the best. This wasn’t a one off, either, as I deliberately took two frames in a row in the hope that at least one of them would come out and both of them did. Whilst they’re clearly not great pictures, they are a great example of what’s possible if you can hold perfectly still!

Whilst I’m impressed by the detail the Lubitel captured, we do need to acknowledge that the lens is downright awful. It flares all over the place with even the smallest hint of sun either in front or to the side of your shot – and I do mean the smallest amount. At first you think you’ve got a light leak but closer inspection of the negative shows the classic signs of flare. Looking at the image above you can see a light patch above the waterfall which is the sun just shining through the trees. This wasn’t a bright day by any means, it was really dark in that part of the woods but you still get this “ghostly” lighting.

There were some frames that I had to apply a nearly 4 stop graduated filter to one side of the image to try and rescue the exposure and even it out across the image. Oh and it definitely does vignette quite badly, but this doesn’t really offend me in black and white images – I’d much rather be able to control the crazy way the light appears to bounce around inside this thing when taking pictures.

Overall, for the money and with your expectations aligned, using the Lubitel 166 is a really quite pleasant experience where you get all the film cliches – slow down, take time composing each frame, don’t waste film – think about each picture before taking it and so forth.

Conclusions and Learning

Yes, I admit, the Lubitel 166u does have a certain charm about it, but then so do most TLR cameras. From launch in the 1970’s to the last few sales in the mid 1990’s, this camera undoubtedly offered an entry point into medium format photography for thousands of people and for that it rightly holds a place in history as a “classic” camera. The fact that anyone who saved up a few quid could step up to medium format, experience those huge negatives for themselves or even just use up some old roll film they’d been given as people transitioned to 35mm has to be commended.

It’s not terrible. Of course, compared to true “Hasselblad standard medium format” it’s awful, but that isn’t the point. The fact that you can get very good, clear and detailed images out of such a cheap camera is impressive in itself. After the first roll of film you learn what you really shouldn’t do, learn to expect the vignette, to ignore the shutter speeds and just guess and to shoot at smaller apertures to ensure everything you thought was in focus is actually in focus. I’m sure there are lots of Lubitel owners who have taken some of their all time favourite images with this plastic box of tricks.

Therefore, it must still be a great entry into the world of medium format.

Not so fast.

You see, we once again arrive at the fact that these days we have a huge amount of second hand choice at rock bottom prices, coupled with the fact that some cameras have really silly second hand prices now and others seem to be completely undesirable despite being far better.

In 1990, you had no choice. You were very, very unlikely to get a lucky deal on a TLR, even second hand and in good condition, compared to the £20 a Lubitel 166U would set you back. If you ventured outside of TLR land you’d have been able to pick up a folding bellows type camera I’m sure, and perhaps that would’ve been a better choice back then despite having to buy a rangefinder or guess your subject distances for each shot.

Today, though, you have lots of choice and although TLR’s are quite fashionable these days, you can get hold of the less popular, but by no means worse, brands and models for the same or less money than a Lubitel will set you back today. When something achieves cult status, it doesn’t suddenly elevate its image quality or usability, so consider carefully why you might want one of these in the first place.

If you want to just try out a TLR on the cheap, spend the time looking around at the many, many TLR cameras that were produced and see which ones are going cheap in your area. You’ll be surprised. Don’t be put off buying Japanese copies as well, by brands such as Halina or Seagull as these will all still produce better image quality than the Lubitel.

However, if you find a 166 and it’s cheap, buy it. You’ll definitely enjoy it.

Share this post: